[ccfic]

Tree, hedgerow and woodland (THaW) ecosystems are key components of the UK’s complex and interconnected ecosystem[1]. All are historically and ecologically important providing crucial habitats and habitat corridors, mitigating against the impacts of climate change, and providing key ecosystem services. However, they are largely at threat from climate change, pests and diseases, and human impacts.

Despite an increase in tree cover over recent years, there has been a continuing decline in woodland wildlife, native trees and ancient woodland across the UK. Great Britain has the lowest tree cover in Europe with only a 12.64% canopy cover[2], of which 2.5% is ancient woodland[3]. During the 19th century, over a quarter of Britain’s hedgerows were lost, with over 120,000km removed and not replaced[4]. Despite recent attempts to reverse the reduction of these ecosystems, they are still exposed to an increasing threat from agriculture, urban development and climate change. With government plans to increase tree species populations by 10% by 2030, canopy cover by 3% by 2050, and create 45,000 miles of hedgerows by 2050, it is vital to monitor, map and manage these habitats[5].

Importance of THaW habitats

THaW habitats are crucial for maintaining biodiversity and provide habitat and migration corridors for species including birds, insects and mammals. These habitats offer food, shelter and breeding sites and support a rich and varied biodiversity.

Hedgerows are vital for pollinators like bees and butterflies, which, in turn, are crucial for agricultural productivity. They play a significant role in climate regulation by sequestering carbon dioxide thereby helping to mitigate the effects of climate change. They can also influence and moderate local climates by reducing wind speeds and increasing humidity.

Looking at urban areas, street trees in particular help reduce the urban heat island effect in cities and towns by reducing temperatures and contributing to more sustainable environments.

All these ecosystems help to conserve soil and water. Tree roots help to stabilise soil preventing erosion, and hedgerows act as barriers reducing the speed of water runoff. This aids in water conservation. Hedgerows, in particular, improve water quality by filtering out pollutants, chemicals and sediments before they reach any water source or water body.

Beyond the ecological benefits, these habitats are culturally and historically valuable. Many ancient woodlands and hedgerows date back centuries and are integral to historical landscapes across the UK. Often, they are used to define property boundaries and are featured in local traditions contributing to local community identities.

Threats to THaW habitats

Climate change poses a significant threat to these ecosystems. Changes in temperature and precipitation patterns are changing habitats, and they have become unsuitable for some species. An increase in extreme weather events such as storms and floods can leave physical damage to trees and hedgerows. Prolonged drought can cause stress and make these habitats more prone to disease and pests.

Invasive species, pests and diseases pose a threat to native tree species. For example, ash dieback and oak processionary moth are two major concerns currently threating UK treescapes. The spread of pests and diseases is exacerbated by changing climates, creating favourable conditions for diseases to thrive.

Urban expansion, pollution and intense agricultural practices have led to habitat loss and fragmentation. Some agricultural practices lead to the destruction of hedgerows, causing a decline in nutrients within the soil which they need to thrive. The removal and reduction of Britain’s hedgerows is reducing biodiversity and disrupting wildlife corridors across the UK, while the use of pesticides and fertilisers harms species and degrades soil health over time.

Importance of geospatial data

Traditionally, field surveys have been undertaken to monitor and map vegetation. These are time-consuming and impractical for large-scale assessments. The significance of geospatial data lies in its ability to provide accurate, comprehensive and up-to-date information across large areas. Harnessing the power of geospatial data can save time and resources, enabling scalable solutions for mapping and measurements.

The high accuracy and precision of geospatial data is crucial for identifying individual trees, delineating hedgerows and measuring canopy cover. Identifying vegetation cover using aerial surveys can aid assessments of habitat connectivity, conservation planning, land management and more. Accurate and up-to-date datasets can be applied as part of regular monitoring, detailed mapping, and analysis of key statistics and spatial patterns.

Geospatial data detailing information about THaW habitats can help identify habitat corridors for restoration and protection. Mapping hedgerows highlights gaps in connectivity that need to be filled to allow wildlife to move safely between habitats. Through analysis of tree cover and carbon sequestration, policymakers can identify key areas for tree planting to help with climate change mitigation. The scalability of geospatial data is particularly beneficial for national and regional assessments and to monitor targets set by the government.

Using geospatial data to monitor changes over time is beneficial for understanding the health of ecosystems, and the effects of environmental policies and practices. Using datasets relating to tree cover enables effective monitoring of efforts to increase canopy cover, with areas easily identified for planting to be increased.

Farmers can apply techniques based on geospatial data to implement sustainable practices, such as hedgerow maintenance to reduce soil erosion, enhancing biodiversity, and to monitor any effects caused by a change in practice. The temporal aspect of geospatial data is critical for understanding long term trends amongst THaW habitats.

Additionally, geospatial data can be used in visualisations and community engagement projects. The data can be visualised in ways that are accessible to schools, community engagement groups and the wider public. Interactive maps can educate the public and raise awareness about the importance of THaW habitats. In turn, this can encourage community involvement in conservation efforts close to their home.

The advantages discussed points to the increasing importance the role geospatial datasets play in everyday mapping, monitoring and management of THaW habitats.

Bluesky vegetation datasets

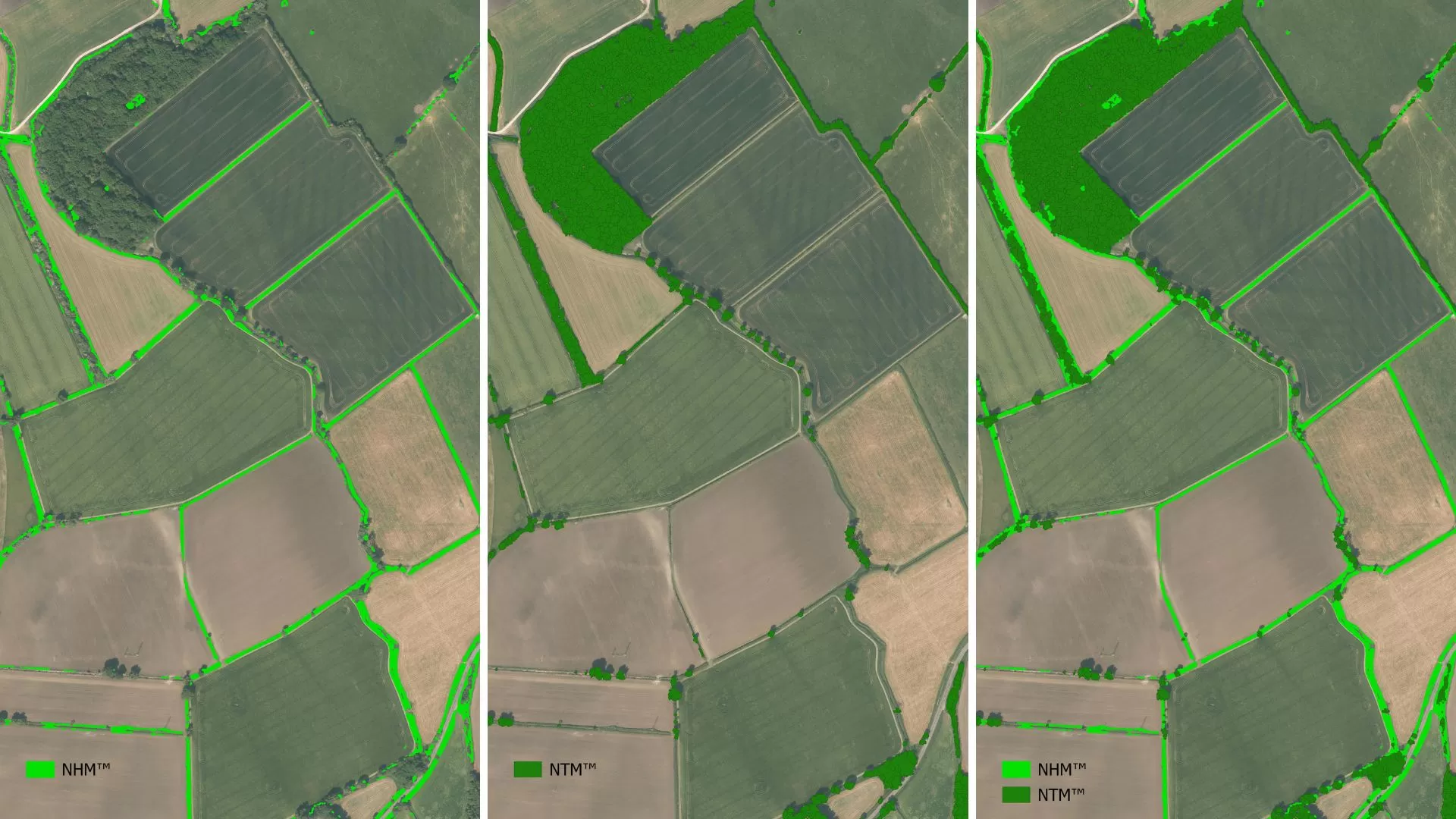

The combination of Bluesky’s National Tree Map™ (NTM™) and the recently launched National Hedgerow Map™ (NHM™) offers a comprehensive geospatial solution to better understand Great Britain’s THaW ecosystems.

NTM™ is the most detailed and up-to-date tree dataset available in Great Britain. It offers complete coverage across England, Scotland, Wales and the Republic of Ireland providing a unique and comprehensive database of location, height, and canopy/crown extents for trees 3m and taller. NTM™ is updated regularly through our cyclic two-yearly update programme, ensuring that it remains the most detailed, comprehensive, and up-to-date tree map available. The dataset is created from Bluesky’s high resolution national aerial photography, accurate terrain and surface data, and colour infrared imagery using innovative processing techniques.

NTM™ is already being used across a variety of sectors including insurance, utilities, forestry, government, planning and environmental management. There is a broad scope of applications for the dataset including carbon capture calculations, urban forestry planning, tree inspection management, tree establishment monitoring, environmental modelling, and many more with new uses regularly being discovered.

Bluesky has used its wealth of expertise in tree mapping to deliver a new product to its geospatial dataset offering – the National Hedgerow Map™ (NHM™). NHM™ provides the location, height, volume, vegetation extent, and the centreline for all vegetation 3 metres and below. A unique offering of volumetric data enables accurate calculations of carbon capture and storage. The dataset has been developed using our high resolution national aerial photography, accurate terrain and surface data, and NDVI (Normalised Difference Vegetation Index). NHM™ is updated through our cyclic two-yearly update programme in line with our aerial photography capture programme, and other vegetation products.

Despite its recent introduction, we are already seeing this new dataset adopted by customers in several industries including government, utilities, and agricultural land managers. Applications for the NHM™ dataset go beyond hedgerow monitoring and mapping. Further applications include flood risk mitigation mapping, planning of wildlife corridors, biodiversity net gain (BNG) planning for developers, carbon storage and above ground biomass calculations, hedgerow restoration projects, and noise mitigation mapping.

When used conjointly, Bluesky’s vegetation products offer a comprehensive understanding of all tree, hedgerow, and woodland ecosystems across Great Britain. The NTM™ provides information on all woodlands, small groups of trees, lone street trees, and hedgerow trees. Complementing this, NHM™ provides information on hedgerow features, and other low vegetation such as orchard trees and shrubs not identified in NTM™. Together these datasets form a comprehensive toolset for effective management, and monitoring of all woodlands, low hedgerows, hedgerow trees, lone trees and other vegetation types.

Conclusion

The integration of geospatial datasets in monitoring and managing THaW habitats is crucial for their conservation. Given the threats they face from climate change, pests and diseases, and human impacts, it is essential to use advanced technologies to help with protection and restoration. Bluesky’s vegetation products provide a comprehensive and powerful dataset for understanding, monitoring, and protecting these habitats. With government plans to increase tree cover, and hedgerow length, the role of geospatial datasets such as NTM™ and NHM™ will become increasingly important to achieve these targets and preserve the natural environment.

[1] Luscombe et al., 2023 (Link)

[2] Bluesky’s National Tree Map, 2024 (Link)

[3] Woodland Trust, 2021 (Link)

[4] Petit et al., 2003 (Link)

[5] DEFRA, 2022 (Link)